influences

The Dalai Lama

I first met the Dali Lama in India in 1970 and have attended his teachings since. He once gave a week-long teaching in Tucson on patience. Over twelve hundred people attended the event at a desert resort.

One day, as the translator translated his commentary on the text, Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, his Holiness interrupted him, saying, “That’s not what I said.” The translator responded, “Your Holiness, it is what you said.” His Holiness again disagreed. They debated in Tibetan, and then H.H located the disputed section in the text. He looked at it and then burst into laughter, “Oh, I made a mistake.” There the Dalai Lama was, caught in an error in front of twelve hundred people, laughing uproariously about it. He is a wonderful role model of a non-constricted heart that comes when we are not defending a certain image of who we are.

S.N. Goenka

S. N. Goenka was an Indian, a former businessman, drawn to meditation to cure his ferocious migraine headaches. He studied Buddhism in Burma and then began leading ten-day intensives in India. Participants lived like monastics: two meals a day and a structured schedule of meditation and instruction.

Outwardly Goenka seemed like an ordinary businessman; inwardly, he radiated something extraordinary. Centered, unruffled, he appeared completely comfortable in his own skin. He was rigorous and demanding in his approach. Yet his kindness and compassion charged the air around him with warmth and light. He laughed a lot, spoke in simple English, and was quite approachable. From Goenka, I learned about pure, impersonal love. It was very clear that he wanted nothing from me. He accepted no money and was clearly not teaching for ego reasons or power.

Munindra

Munindra was an Indian teacher who lived in Bodh Gaya after many years in Burma. Whimsical and elfin, he dressed all in white and resembled Gandhi. His relaxed teaching reflected his favorite saying, “Just be simple and easy about things.” He taught that every action in our lives can be meditation. Children gathered around him spontaneously, especially when he stopped to rejoice at the sight of a tree or a flower or an animal.

Early on in my practice, Munindra said to me, “The Buddha’s enlightenment solved the Buddha’s problem, now you solve yours.” This was very important for me…it felt like the first time someone looked me in the eye and basically said, “You can do it. You can solve your problem.”

Dipa Ma

Dipa Ma was a little bundle of a woman wrapped in a white sari with a huge psychic space, radiating light and peace. She had been a student of Munindra. To visit her in Calcutta, one walked through the filth of a slum alley and climbed four flights of steps up to the tiny room Dipa Ma shared with her daughter. The room was nearly bare, with only a wooden bed and some clothes hung behind a curtain. Dipa Ma greeted us lovingly and quietly. Sometimes she would answer questions or offer us food. We would always leave her presence filled with a transcendent sense of well-being. I often found her sitting cross-legged on the wooden bed in the corner of her room. Greeting me, Dipa Ma would take my head in her hands, stroke my hair, and whisper, “May you be happy, may you be peaceful.” Over tea, as we discussed my meditation practice, she would gently push me beyond my self-imposed limits. “You can do it.” “Sit longer.” “Be more diligent.”

Kalu Rinpoche

Kalu Rinpoche was near Darjeeling, India when I first studied with him. My home was a shack on a top of a hill with no solid roof or walls. I received only one meal a day. My water source was a stream at the bottom of the hill. During the monsoon, I had to wrap my hut in sheets of plastic. Kalu Rinpoche inspired me to try to bring teachings on generosity, patience and renunciation into every day.

Kalu Rinpoche taught, “If a hundred people sleep and dream, each of them will experience a different world in their dream. Everyone’s dream might be said to be true, but it would be meaningless to ascertain that only one’s person’s dream was the true world and all others were fallacies. There’s truth for each perceiver, according to the karmic patterns conditioning their perceptions.”

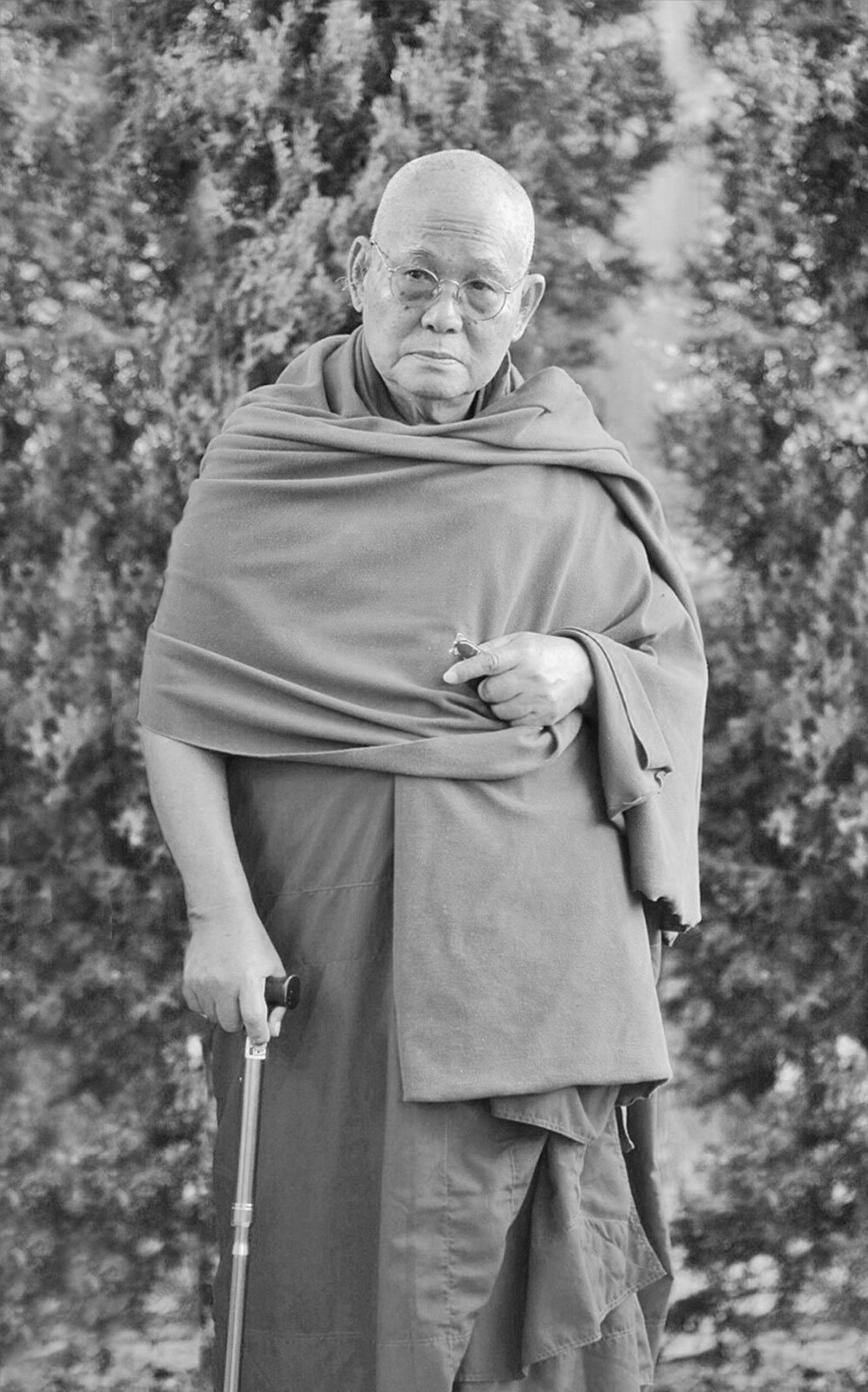

Sayadaw U Pandita

I first met Sayadaw U Pandita when he came to Barre to teach a three-month retreat. As a student, I diligently wrote down brief notes after each period of sitting and walking meditation. I wanted to describe my experiences clearly in our interviews. When I began relating my experiences, U Pandita said, “Never mind that. Tell me everything you noticed when you put on your shoes.” I hadn’t really paid attention to putting on my shoes. He told me to try again. The next day I went into my interview ready to report on my practice and my experience while putting on my shoes. U Pandita said, “Tell me everything you noticed when you washed your face.” I hadn’t really paid any attention to washing my face. Every day U Pandita would ask me a different question. Soon I was practicing mindfulness in everything I was doing. I discovered that when I stopped resisting this continuity of awareness, it opened up a deep and clear understanding of what meditation actually is.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche

I went to Nepal in 1991 with several friends to try to study with Rinpoche in the hills above Kathmandu. We had hired Sherpa who were going to set up camp for us on the grounds of the nunnery and cook for us. When we got to Kathmandu, we discovered that Rinpoche’s wife was very ill and he was instead in nearby Bodhinath. Our sherpas set up camp on our hotel grounds (the easiest trek they’d ever done they said) and we studied with Tulku Urgyen every day. He was so generous to us, taking the time to see us. His teachings were life changing. I have the greatest respect for his sheer ability to teach. There was nothing short of brilliance in his presentation, his urging of his students to have confidence in their own experience, his cutting through our clinging or confusion. All of this was executed with beautiful simplicity and elegance. “How in the world did he seem to convey the whole sweep of the Dharma,” I would ponder, “with just a photo and his handkerchief as props?”

Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche

Nyoshul Khen Rinpoche lived in Paris when I first met him. The room was alive and vibrant with Khenpo laughing, teasing and playing with the children. The moment I saw him a constriction in my heart eased, one that I hadn’t even realized was there. He looked up at me, and as soon as our eyes met I felt I’d come home. The light I sensed coming out of him was brighter than ever the most extravagant color of the walls surrounding us. Khenpo was the most spacious person I’d ever met. It seemed as though the wind passed right through his translucent being. Many times in his company I had the strange sense we were standing in a wide open field, great empty expanses spreading out in all directions. Yet he was entirely unself-conscious like a magician unattached to his own magic. He taught me that in letting go of our desires for acquisition and performance, we can just let the mind rest in ease. As he would put it, “Rest in natural great peace, this exhausted mind.”

Tsoknyi Rinpoche

Tsoknyi Rinpoche is one of the sons of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. He was 25 when I first him. On his first visit to North America, he led a two-month retreat in New York state. He used his considerable talents as a mimic to display the differences he noted between people from Argentina, Germany and the United States. Even then I felt his special gifts as a teacher. I find him brilliant, and funny, and increasingly so.

As reflection of his dedicated caring for others, Rinpoche engages in a wide variety of projects supporting monks and especially nuns, in Nepal and Tibet. He once told a story about the eminent Dilgo Khentse Rinpoche giving an initiation to two people with the same dedication and intensity he would exhibit if there were 2,000 in front of him. One of the things I admire in Tsoknyi Rinpoche is that he will pick out an extraordinary quality to admire in another.